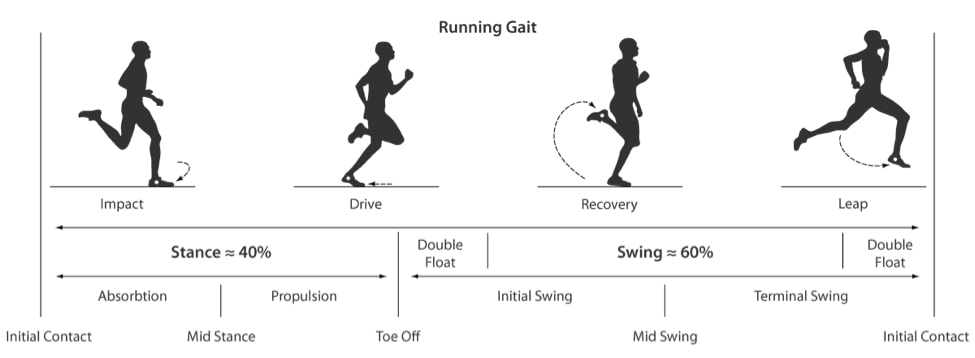

To maximise your outcome after a hamstring injury, it is vital to consider how you run and if this is contributing to your risk of injury. We know from research studies that the hamstring is most commonly injured during the terminal swing phase of running where the leg is extending forward preparing the foot for contact (Schache et al., 2012). (Figure 1.)

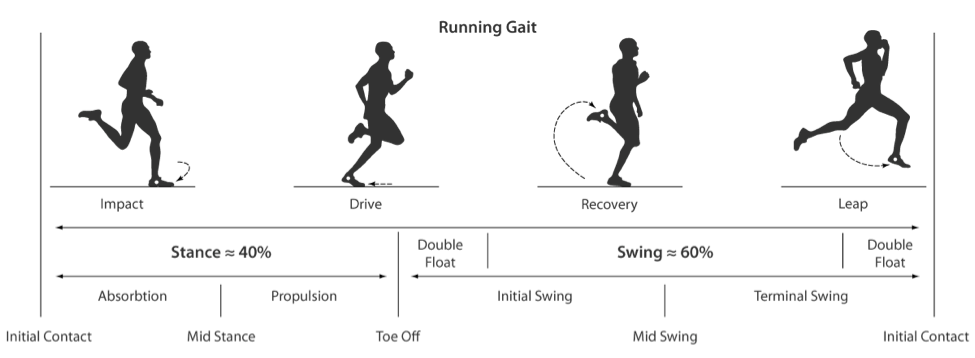

Figure 1: Running Gait Cycle In this phase, the Hamstring muscle complex is actively lengthening, (Figure 2) followed by a very rapid and forceful contraction. It is here, where the hamstring is vulnerable as often it will be placed under excessive strain beyond which it can tolerate, especially at higher running intensities, such as sprinting.

Figure 2: Peak hamstring lengthening during terminal swing (Schache et al., 2013) Rehabilitation should therefore mimic these biomechanics, so it is important to strengthen the hamstring with high loads, speed and in lengthened positions. Research indicates that hamstring rehabilitation using this lengthening model results in substantially quicker return to sport compared to a more conventional program of stretches, cable extensions and single leg bridges (Askling et al., 2013).

Rehabilitation Goals

- Settle acute injury and prevent further damage: Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation (RICE)

- Commence low load hamstring activation exercises, pain free.

- Restore hamstring flexibility equal to other side

- Restore hamstring strength

- Strengthen hamstring in lengthened positions, incorporating high speed/power exercises that are essential for the mechanics of running and sport.

- Address other possible contributing risk factors for injury – eg. Pelvic/core weakness, running technique

- Ensure adequate running program and gradual return to training before returning to sport.

Referring back to the previous Hamstring post (8 Key risk factors for Hamstring injury), persistent strength deficits post hamstring injury is a modifiable risk factor. By having a structured and appropriate rehabilitation program specific for the injury and sport can optimise an athlete’s recovery, whilst hopefully minimising future recurrence risk. For any further enquiries, or if you have a troublesome hamstring, don’t hesitate to contact us.

References

Schache A.G., Dorn T.W., Blanch P.D., Brown N. & Pandy M.G. (2012). Mechanics of the Human Hamstring Muscles during sprinting. American College of Sports Medicine, p 647 – 658. Schache A.G., Ackland D.C., Fok L., Koulouris G. & Pandy M.G. (2013). Three-dimensional geometry of the human biceps femoris long head measured in vivo using magnetic resonance imaging. Clinical Biomechanics, p278-284 Askling C.M., Tengvar M. & Thorstensson A. (2013). Acute Hamstring injuires in Swedish elite football: a prospective randomised controlled clinical trial comparing two rehabilitation protocols. British Journal of Sports Medicine, p1-8.